“I started practicing on Dvořák.” Mařatka’s sculptural portrait of the composer

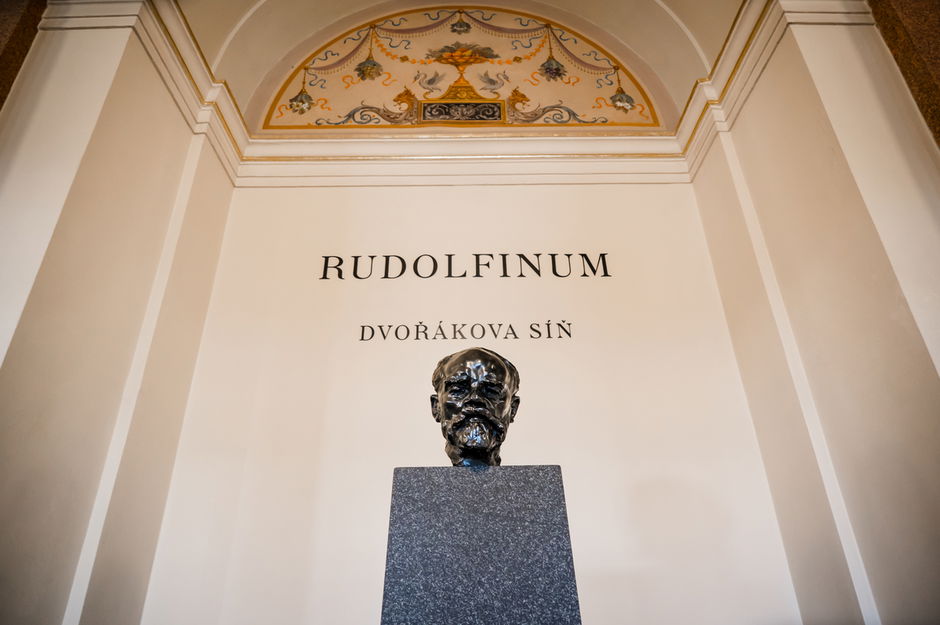

In the foyers of all floors of the historic National Theater building, the audience can count around eighty busts of important cultural figures. Rudolfinum visitors can count only one, the portrait of Antonín Dvořák by Josef Mařatka. A stand-alone piece of art is completely unostentatious. Its power lies in the quiet concentration the intensity of which suggests the greatness of the composer in the portrait and the sculptor himself. What makes this bust so different from others?

24.11.2023

|

Author: Jan Kachlík

On the Rudolfinum’s first floor near the main entrance, there is Antonín Dvořák's head bowing with closed eyes on a dark stone plinth. The author of this masterful portrait, sculptor Josef Mařatka, was a generation younger than Antonín Dvořák although they both had a lot in common: artistic talent, diligence, humility, but also life fates.

The “House of Artists” in Žitná Street

In the fall of 1877, Antonín Dvořák and his wife moved to the house in Žitná Street No. 10 (now No. 14), just a short distance from their previous residence in Prague. What the composer also liked about the place was the fact that none of the tenants had a piano, an instrument that had disturbed him so much during compositions at the previous address. At that time, he had no idea that the number of artists in the house would gradually increase. Nor did he know how many famous personalities would visit him at this address. Just out of composers: Brahms, Grieg, Tchaikovsky or Janáček as well as others.

Just three years before the arrival of the Dvořák family, son Josef was born in this house on May 21, 1874 in the Mařatka’s family and, a year later, the Koldovský family had daughter Růžena who became an important opera singer later on. Shortly after their births, these children would grow up together with the Dvořák's and the palatial house with a spacious yard provided them with many opportunities for various games. When the noise became unbearable Mrs Dvořáková, Dvořák’s wife, called them out. Sometimes, she would just throw coal on the patio at the Mařatka’s place and the children knew that they had to be quiet as Dvořák was composing.

© National Museum - Czech Museum of Music, inv. no. 6049 I1, photograph of the house in Žitna Street where Dvořák lived, 1901, author unknown

Ukázat další fotografie

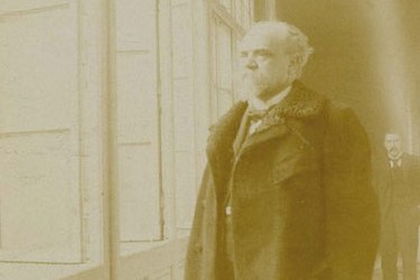

Dvořák on the pavilion, Josef Suk in the background

© National Museum - Czech Museum of Music, inv. no. S 226/1071, Antonín Dvořák on the pavilion of a house in Žitná Street, Josef Suk in the background, ca 1902, author unknown

1 / 2

House in Žitná street

© National Museum - Czech Museum of Music, inv. no. 6049 I1, photograph of the house in Žitna Street where Dvořák lived, 1901, author unknown

2 / 2

Dvořák on the pavilion, Josef Suk in the background

© National Museum - Czech Museum of Music, inv. no. S 226/1071, Antonín Dvořák on the pavilion of a house in Žitná Street, Josef Suk in the background, ca 1902, author unknown

There was also another tenant working diligently in the house – the painter Jaroslav Věšín whose studio the young Josef Mařatka often enjoyed visiting. He was attracted to work-in-progress paintings, art magazines, and all of this inspired creation of his own drawings. He was also musically talented though. Therefore, on Dvořák’s recommendation, Josef’s parents bought him a piano which he was only allowed to practice on when the composer was not working. Later on, he began learning to play the violin and the flugelhorn, which had caught his attention during the military bands’ parades on nearby Charles Square.

When Josef did not get into a teacher's institute after finishing the citizen school (a type of lower secondary school in then Austria-Hungary) he went to admission exams at conservatory with Dvořák’s visiting card containing his recommendation. This time, he finally succeeded and was able to register right for the flugelhorn. After that, however, he was lured by a friend to the recently founded School of Applied Arts, which, like the conservatory and to Mařatka’s tremendous joy, did not teach mathematics. With his talent for painting, he passed the exam with flying colors and, in the end, gave preference to visual art before studying music. He did not apply for painting though, but instead for sculpture as he took his neighbor Věšín’s advice: “There are lots of painters and much fewer sculptors”.

“Even when in Prague, I admired Rodin’s works in reproductions”

At the age of fifteen, Josef Mařatka began studying in Prague, first supervised by the professor Celda Klouček, then in the Josef Václav Myslbek’s studio. After receiving benefactor Hlávka’s scholarship for the Ledaři na Vltavě (“Ice Miners on the Vltava river”) sculpture, he went to Paris in 1900 which served as a gateway to the world of fine art contemporary trends for the young artist.

The labyrinth of an overabundant offer was navigated by Mařatka with great intuition. After all, he already had sufficient general knowledge at that time: “Even when in Prague, I admired Rodin’s works in reproductions.” He was therefore happy when he got a chance to view the results of thirty years of work by this adored sculptor Auguste Rodin in his private pavilion. He knew who he wanted to be supervised by, but, at the same time, he also barely understood French, had hardly any money, and recognized the relentless reality of life contrasting with his ideals.

In his memories of Paris, Mařatka wrote down in detail his futile efforts to get close to Rodin and summed them up eloquently as follows: “I had already had my new acquaintances and I was eagerly and constantly asking them, mainly what anyone knew about Rodin. I only kept hearing how difficult it was to get to him, it was completely impossible as the French themselves, the sculptors confirmed to me. Everyone knows him, but only tells me about him from a respectful distance. How hard it is to get to Rodin, I already know well.”

After many vicissitudes, the young Mařatka, with the help of friends and intermediaries, finally and almost miraculously managed to achieve his dream goal and was accepted into the studio of perhaps the most famous sculptor at the time. He cherished the opportunity even more when, even as Rodin's pupil, he began explorations of hands and feet, body movement and its metaphorical contents. Through drawings and models, he pondered questions concerning the connection of body and soul more and more deeply.

Soon, Mařatka managed to become Rodin’s assistant and won his personal favor, thanks to which he was able to become one of the main organizers of the famous exhibition of Rodin's works in Prague in 1902. The event was attended by the French sculptor himself who, at that time, was already seen as a modern Michelangelo. At first, Rodin was reticent about the magnificently conceived event, but, in the end, he made very fond memories of his trip to Bohemia and he also visited Moravia in addition to Prague.

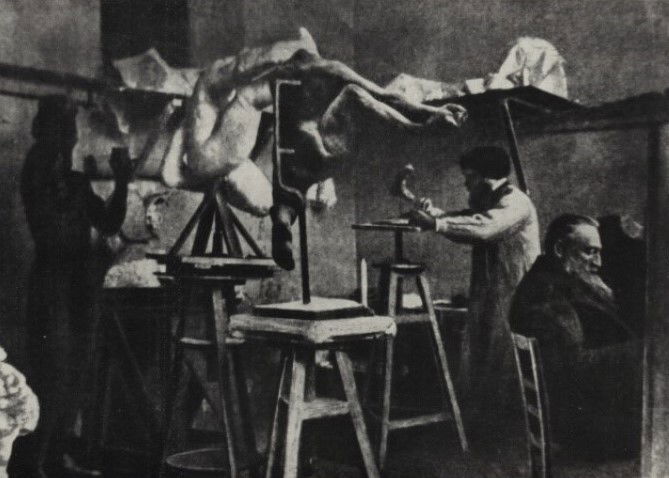

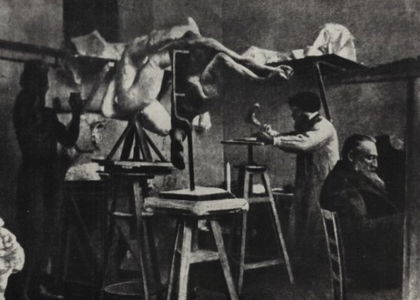

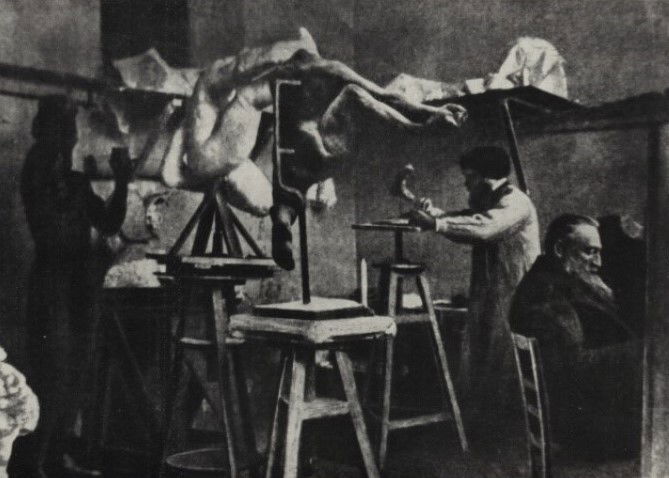

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin in the art studio

Source: MASARYKOVÁ, Anna. Josef Mařatka. 1st edition. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, 1958

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

Ukázat další fotografie

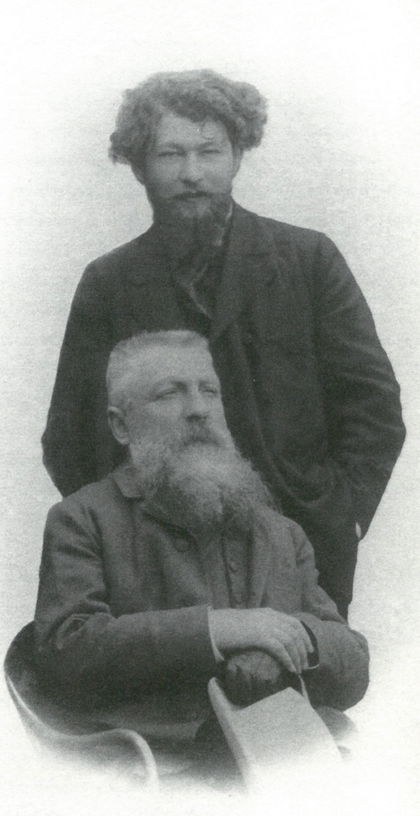

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin

Source: MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznamy. 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

Josef Mařatka in Paris, 1902

Source: MASARYKOVÁ, Anna. Josef Mařatka. 1st edition. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, 1958

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin, group photo

Josef Mařatka Source:MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznamy, 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

Josef Mařatka in Rodin's art studio

Source: MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznay. 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's heirs.

1 / 5

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin in the art studio

Source: MASARYKOVÁ, Anna. Josef Mařatka. 1st edition. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, 1958

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

2 / 5

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin

Source: MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznamy. 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

3 / 5

Josef Mařatka in Paris, 1902

Source: MASARYKOVÁ, Anna. Josef Mařatka. 1st edition. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, 1958

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

4 / 5

Josef Mařatka and Auguste Rodin, group photo

Josef Mařatka Source:MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznamy, 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's inheritors.

5 / 5

Josef Mařatka in Rodin's art studio

Source: MAŘATKA, Josef. Vzpomínky a záznay. 2nd edition. Prague: Karolinum, 2003. ISBN 80-246-0518-x.

Published with the permission of Josef Mařatka's heirs.

“Spirituality that must not stay on the surface”

Josef Mařatka stayed in Paris for another two years and returned to Prague in 1904 right when Antonín Dvořák died. At the request of Dvořák's family, Mařatka made a copy of his face after the composer’s death and made a cast of his right hand. All this in his own native house in Žitná Street. For the thirty years old Mařatek, this strong personal experience also represented the beginning of thinking about Dvořák's sculptural portrait.

Mařatka worked on the bust for several years and put all his skills into it. He himself later wrote a note on this creative phase: “I started practicing on Dvořák” and this work “certainly differs from my pre-Paris works”. It is “a manifestation of Rodin’s teachings – modellings from all sides, from all profiles – spirituality that must not stay on the surface”.

From the first sketches of lengths of a few centimeters, Mařatka arrived at the first modeled exploration in 1905. Concurrently, another one, a completely differently conceived exploration was created in which Dvořák's head was made to almost lay down and listen intently. Between 1905 and 1911, Mařatka continually created nine versions of Dvořák's bust in total that are located in several institutions and galleries today. The final creations include the bust for the National Theater and the last version (1910–1911) which has a place of honor in the form of a bronze specimen at Rudolfinum in Prague.

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

Ukázat další fotografie

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

© Lucie Krejzlová

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

© Lucie Krejzlová

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

© Lucie Krejzlová

1 / 4

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

2 / 4

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

3 / 4

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

4 / 4

Bust of Antonín Dvořák at the National Theatre

Mařatka's ultimate version of the Antonín Dvořák’s sculptural portrait, unlike the previous versions, was created only in the form of a head without shoulders and chest although significant and deeper differences are apparent in his facial expression. In Mařatka’s early exploration from 1906, according to Wittlich, “a more passive introspection or listening prevails. The last version from 1910–1911, however, has a much more energetic handwriting, the dynamics of matter, and the feature of creative activity prevails in it.” And this is exactly how Antonín Dvořák was described by his contemporaries, as a creative person who literally thinks through music. For example, Marie Červinková-Riegrová, a great observer of people, wrote in her notes in 1881:

“I like Dvořák. He is extremely good-natured and natural. A musician in every vein [...], he suddenly thinks and stops talking. He is passionately in love with music and is convinced that it is the best thing in the world. When he discusses some music, the deep furrow dividing his forehead deepens even more […]. Dvořák does not think about himself, fame in the world had no effect on him, he has remained as natural as he was before. He seems to be zealous in everything he does.’

Mařatka was also enthusiastic and worked on Dvořák for several years with great creative enthusiasm. He managed to capture Dvořák as a living creator, in a moment of complete concentration. In a moment when it is appropriate to be quiet because Dvořák is composing.

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

Ukázat další fotografie

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

© Lucie Krejzlová

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

© Lucie Krejzlová

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

© Lucie Krejzlová

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

© Lucie Krejzlová

1 / 5

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

2 / 5

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

3 / 5

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

4 / 5

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

5 / 5

Bust of Antonín Dvořák in Rudolfinum

When the prominent Czech photographer Josef Sudek (1896–1976) documented Mařatka’s work for the purpose of professional monographs on this sculptor, he also approached this work in a creative way. “Modeling is alive and must be photographed as alive,” he said in one of interviews. This advice may also provide a useful key to solving the question of what Mařatka tells us about the great composer.

The presence of Antonín Dvořák's bust in the Dvořák Hall foyer at Rudolfinum is perhaps so obvious to us that it doesn't even need to arouse our curiosity and interest anymore. The sculptor Josef Mařatka also naturally knew a generation older Dvořák for many years – as one of the neighbors in the house. Nevertheless, he created a completely unconventional and extraordinary portrait. He knew very well why he had to refrain from remaining on the surface when working on Dvořák.

Sources and literature

- ČERVINKOVÁ-RIEGROVÁ, Marie, VOJÁČEK, Milan, ed. and VELEK, Luboš, ed. Zápisky. Edition 1. Prague: Národní archiv, 2009, p. 157

- DOBRINČICOVA, Jaroslava. Ikonografie Antonína Dvořáka. Hudební věda. Prague: Academia, 2011, 48(4), 325-360

- Josef Mařatka a Auguste Rodin v Praze 1902. Prague: Vysoká škola uměleckoprůmyslová, 2002. [6] p.

- MAŘATKA, Josef a Petr WITTLICH. Vzpomínky a záznamy. Prague: Karolinum, 2003, p. 34

- MASARYKOVÁ, Anna. Josef Mařatka. 1st edition. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, 1958. 85 pages, 161 pages of unnumbered visual attachments. Současné umění; 23rd volume

- SIBLÍK, Emanuel. Josef Mařatka. Prague: Jan Štenc, 1935, pp. 69–70

- SUDEK, Josef et al. Sudek a sochy. 1st edition. [Prague]: Artefactum – Ústav dějin umění Akademie věd České republiky, 2020. 619 pages

- VLK, Miloslav. Antonín Dvořák ve výtvarném umění. Prague: Středočeská galerie, 1984. Unpaginated.

- WITTLICH, Petr. Poselství z hlubin: Interpretační poznámky k bustě Antonína Dvořáka od Josefa Mařatky. Hudební věda. 1992, 29(2), 128–129

- [online]. Available from: Šupka, Ondřej: https://operaplus.cz/minulost-a-budoucnost-dvorakova-domu-v-zitne-ulici/?pa=2 [cited on 14 March 2023]